From an Ancient Bamboo Grove to Modern China

2009-05-31 14:11:22 KEN JOHNSON

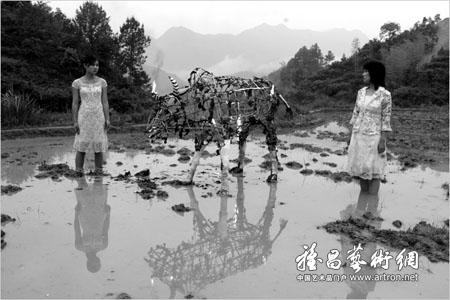

A scene from Yang Fudong’s “Seven Intellectuals in a Bamboo Forest,” at the Asia Society.

The celebrated filmmaker Yang Fudong, who was born in 1971 and lives in Shanghai, is having a New York moment. His best-known work, a beautiful but tryingly long, slow and portentous series of movies called “Seven Intellectuals in a Bamboo Forest” (2003-7), is on view in its five-hour entirety for the first time in a United States museum (at the Asia Society).

Meanwhile, Marian Goodman Gallery is presenting Mr. Yang’s “East of Que Village” (2007), a kind of gritty, anthropological study shown as six simultaneously running videos. Seen together, these exhibitions afford a supremely stylish and at times frustratingly narrow glimpse into the collective soul of modern China.

The two projects are similar in some ways. Both are in black and white and proceed with no regard for linear narrative. In terms of subject matter, however, they are worlds apart.

In its snail’s pace, emotional muteness and velvety grain, “Seven Intellectuals,” which was featured at the 2007 Venice Biennale, calls to mind early films by Jim Jarmusch, whom Mr. Yang has credited as an inspiration. Mr. Yang is often a striking image maker, but he has none of Mr. Jarmusch’s zany humor and storytelling imagination. He has also been influenced by the French New Wave.

But his movies, which tend to be wordless, are more pictorial than cinematic. Trained as a painter and photographer, he creates sequences of images that are like perfectly composed Modernist photographs. Often the imagery plays on classical Chinese paintings as well.

Inspired by a story about some third-century Taoists who retreat from the corruption of urban life and government service to a bamboo grove for conversation, singing and drinking, “Seven Intellectuals” tracks the dreamlike meanderings of a group of morose, well-dressed, fashion-model-pretty young people (five men and two women). We first encounter them reclining in the nude on a rocky outcrop on Yellow Mountain in Anhui Province. Then we follow them to a claustrophobic city apartment, where romantic and sexual complications ensue, and then to a beach where they process dried fish and wander over oceanside rocks carrying suitcases.

The last and longest segment has them in a big city, where Mr. Yang’s disjunctive imagery becomes increasingly surrealistic. Though usually dressed to resemble mid-20th-century French philosophers, Mr. Yang’s seven intellectuals look more like graduate students than serious thinkers, and they seem to be without solid foundations of selfhood.

In Part 3, as if to atone for their rootless self-absorption, they take up mountainside rice farming. Barefoot and in peasant clothes, they churn flooded paddies with a rudimentary, ox-drawn plow; build dikes of mud with hoes and pitchforks; and plant seedlings. Like Marie Antoinette and her fellow mock-shepherds, and like American hippies who escaped to rustic communes in the 1960s, these intellectuals indulge in the fantasy of a more wholesome lifestyle and greater intimacy with nature. Of course, it doesn’t last; that kind of life is too hard. Eventually they descend from their high-minded privations to the moral confusion of city life.

Going from the earlier project to the documentary video “East of Que Village,” it looks as if Mr. Yang were doing Social Realist penance for his prior infatuation with privileged youth. Running concurrently on six high-definition flat screens in a dark room, each 20-minute video shows shifting views of a remote village in a region surrounding Beijing. In the desolate landscape outside the village, scrawny dogs forage for food and get into snarling fights. In town we see people doing routine activities. At one point they enjoy an outdoor performance of screechy folk music and a communal parade.

The video suite is not overtly message-driven. Mr. Yang’s minimalist style works as a gaze of all-over, noncommittal attentiveness. By showing six channels simultaneously, he creates an enveloping experience, which is enhanced by the sounds of barking and growling, blaring music and other ambient noises.

In their reticence, Mr. Yang’s films border on pure and nearly static formalism. (He makes “Last Year at Marienbad” seem like an action film.) Nevertheless, they are richly allusive. You can read “East of Que Village” as an allegory of life on the fine line between civilization and savagery. The title, by the way, refers to the direction of the only road leading to the outside world.

Viewed against a backdrop of recent Chinese history — the decline of Maoism, the rise of capitalism, the accelerated importation of Western art and culture — both films exude a mournful ennui that is the opposite of go-go modernity. Welcome to China. Here are the educated classes who aspire to the intellectual and material rewards of modern, global culture, but risk losing their traditional sources of identity and spiritual energy. And there are worlds where life is unforgiving, and death is always near at hand. The future seems bleak.

Click to Browse the Chinese Version(责任编辑:李丹丹)

注:本站上发表的所有内容,均为原作者的观点,不代表雅昌艺术网的立场,也不代表雅昌艺术网的价值判断。

吕晓:北京画院两个中心十年 跨学科带来齐白石研究新突破

吕晓:北京画院两个中心十年 跨学科带来齐白石研究新突破 翟莫梵:绘画少年的广阔天空

翟莫梵:绘画少年的广阔天空 春雨斋主人房茂梁:“好运气”的90后古玩经纪人

春雨斋主人房茂梁:“好运气”的90后古玩经纪人 一级文物逾半数!部分仅展20天!辽博秋季大展聚焦古代文人的园中雅趣

一级文物逾半数!部分仅展20天!辽博秋季大展聚焦古代文人的园中雅趣

全部评论 (0)